Note: I visited Vancouver and toured wineries in western Canada in September 2019 and planned to publish this article in early 2020, to inspire wine-lovers who might be considering a Canadian tour this year. Part-way through the writing, Covid-19 suddenly appeared, and the idea of travel in 2020 became increasingly improbable. It’s taken me two months to return to these treasured memories, and I share them with you now because I believe that the power of armchair travel is to pull us beyond our daily routines, to help us dream of ways to see and do things differently. It’s that kind of creative thinking that will help us move forward.

See also: My Okanagan Winery Picks

Canada is a relatively young nation, but its wine industry – like California’s – has a surprisingly long history. I knew of its wines, but until September 2019 I knew very little about them and had rarely tasted them.

Canada is famous for ice wine. It is the world leader, producing one million litres from Vidal, Riesling and Cabernet Franc grapes, so when I heard in January that the mild winter would mean no Canadian ice wine this year (ditto for Germany), my heart went out to these wineries. Little did we know an extraordinary drop in wine consumption worldwide, due to the pandemic, might be a bigger worry in 2020. And now I am holding my breath for these wineries, which had a good 2019 export year, according to recent OIV global industry wine statistics:

I don’t know where they’re shipping it, but Canada somehow increased exports by 40 million liters in 2019. That’s more than 53 million exported bottles of Canadian wine! Oh Canada! With glowing hearts we see thee rise!

W. Blake Gray, Wine-Searcher.com, https://www.wine-searcher.com/m/2020/04/next-in-sport-worldwide-wine-trends

Beyond ice wine

Nevertheless, ice wine was about all I knew of Canadian wines last September and it appeals to me only in small quantities, so when I toured British Columbia’s Okanagan and Similkameen valleys in the west of the country it was to learn what else is produced and what the wines are like. I found a thriving, organized and well-promoted wine tourism industry, young cellars in swank buildings making a large quantity of what is called premium wine, mostly made to appeal to a mass market. Storytelling is the buzz word, so they all have stories about the winery and sometimes the wines.

Happily, this is Canada, and wine marketing is not as in your face as it is in the US, but it can be frustrating at times for someone who has some basic knowledge of wine. I had the feeling that many of the wineries focus on giving wannabe drinkers starter lessons, along the lines of “a Canadian Pinot Gris tastes like this.” The region has long been a fruit centre although some of the fruit farms that dot the pretty landscape have been or are being converted to wineries.

When you come from a country like Switzerland that is terroir-driven and has been producing wine for centuries, where so many people grew up helping grandpa harvest the grapes (and snacked on them, so pickers know a Gamay from a Chasselas grape), and where much of the focus is on small, beautiful, hand-crafted wines, this is what you tend to seek elsewhere. In larger wine-producing countries I swim as quickly as I can through vats of popular wines made to bulk recipes and sold in large quantities, in my quest for wines and cellars where the product is not simply a commercial one.

Wine isn’t just about drinking. The eternal question for me is: will I find wines created with the ages-old notion that wine is a blend of the land, the people who work it and their culture?

Red blends, cool whites, lakes and a desert

Canada is a large country with a wine region comparable in size to Switzerland’s. And yes, it has it all: the recipe-wines sold at prices that won’t shock, but also real wine gems. I did find some, and they were worth the effort and the slightly higher prices. Among the happy Okanagan surprises for me: a deep, rich and velvety red blend at a winery that sells only to club members; a desert – yes, a desert! – on the fringes of British Columbia that is home to a sustainability-oriented winery with which I fell in love; an admirable sense of First Nation (Canada’s name for the indigenous population) social responsibility at some wineries that set an example for the rest of us.

I even found a Chasselas with a fun story and confirmed what they had heard, that the grape originated in Switzerland. I admired lakes and valleys whose climate and geology forced me to rethink some aspects of producing grapes.

First, Canada’s wine regions and weather

Canada has four official wine regions: British Columbia, Ontario, Québec and Nova Scotia. It is a cool climate wine country, with all growing areas located at 41 to 50° North. British Columbia is the furthest north, with Vancouver at 48.23°N. By comparison, Sion, Valais, in the centre of Switzerland’s largest wine-producing region, is at 46.23°N; Zurich 47.36°N.

Vancouver, a food-lover’s dream city

Another comparison: Valais has only 650 mm of rainfall annually, compared to 900 mm in Geneva and 1600 mm in Ticino. The eastern end of Valais, Salgesch/Salquenen to Visp, is much drier (a mere 295 mm a year) than around Martigny in western Valais, so the average hides the extremes. British Columbia, on the Pacific shoreline, brings to mind rain, but its averages also hide extremes: Vancouver’s annual precipitation is 1,283 mm, Kelowna on Okanagan Lake gets 347 mm and towns to the south have 200 mm, sometimes less, which qualifies them as being part of a “pocket desert”.

Just 40 years of contemporary wines

The country’s official wine web site, Wines of Canada, points out that some of the first grapes in North America were cultivated in Nova Scotia in the 17th century, but its “modern wine history” is only about 40 years old, with much of the boom happening in British Columbia. Canada has a total planting of 12,540 hectares (slightly less than Switzerland’s 14,748 ha in 2017) and 671 wineries.

British Columbia (BC) has 4,249 hectares of vine (a bit less than Valais) and Ontario has 6,900 hectares; together they make up 98% of the country’s premium wine growing area.

BC in 1990 had just 17 wineries and today there are more than 275. History gives us the explanation: the government funded a programme to pull up virtually all vines in 1989, replacing high-yield North American grape varieties and hybrids with European Vitis vinifera grapes.

Inside BC, scaling down again, the Okanagan Valley is far and away the largest of the nine BC wine areas. The wineries benefit from their relative closeness to the international foodie centre of Vancouver: Kelowna, on Okanagan Lake and the main town in the area, is four hours from the city. The Valley covers far more than just the slopes around the edge of the lake, yet it’s easy to do a loop that includes some of the smaller wine areas, including these:

An ever-changing panorama, the Valley stretches over 250 kilometers across numerous sub-regions, each with different soil and climate conditions suited to a growing range of varietals. Cooler climate varieties like Riesling, Pinot Gris, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir thrive in the North Okanagan, while the South Okanagan provides ideal conditions for ripening Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Syrah/Shiraz. The Okanagan Valley has two sub-appellations, the Golden Mile Bench established in 2015 where 791 acres of vineyards are sited on an alluvial fan that was deposited during the last glacial episode. In 2018, Okanagan Falls was identified as the second sub- appellation of the Okanagan Valley and there are more in process.

– Wines of Canada

The grapes

BC claims to grow some 60 grape varieties. Switzerland says more or less the same, but the difference is that Switzerland has several native grapes that it has been growing for centuries, mainly in Valais, as well as some international grapes. The Okanagan Valley has a good variety of grapes and the focus is on international wines, with a sense of let’s try this, let’s try that. If your region is only 40 years old, this is probably what you have to do. In terms of identity, it complicates things for the consumer. Clarity magazine notes that the second generation of wine producers is focusing on quality, after an initial phase of experimenting with different grape varieties.

Swissness

Before I leave behind Switzerland and comparisons: I kept finding odd Swiss links in the Okanagan, the first of which was a beautiful lunch on the terrace of Quail’s Gate, where the wine list included a Chasselas blend, to my great surprise. This most Swiss of wines, grown in so few places outside of Switzerland, arrived here by accident, a classic story of a grower thinking he was buying one grape and three years later, when the vine reached maturity, discovering the nursery had made a mistake or topped up the order with a maverick grape. Near to Switzerland: the bell at the classy Kelowna Mission Bell winery, made by a bellmaker in Annecy, near Geneva. Yet more Swissness: on arriving at Burrowing Owl winery not far from the Oregon border, one of the first things I noticed was a sign about its use of solar power – they are working with a Swiss company!

Merlot grapes, Vanessa, used in their excellent Meritage wine

Mission Hill Pinot Noir

Gray Monk grows several white grape varieties

BC vineyard glossary

Acres to hectares: Canada is more metric than the US, but land is routinely discussed in acres, occasionally with hectares thrown in for good measure. If you want to know how many hectares a winery has, 1 hectare is 2.47 acres. As rough guides: Vanessa Vineyards’ 75 acres equals 30 hectares, Gray Monk’s 45 acres around the cellar gives us 18 hectares, equivalent to a mid- to large Swiss winery.

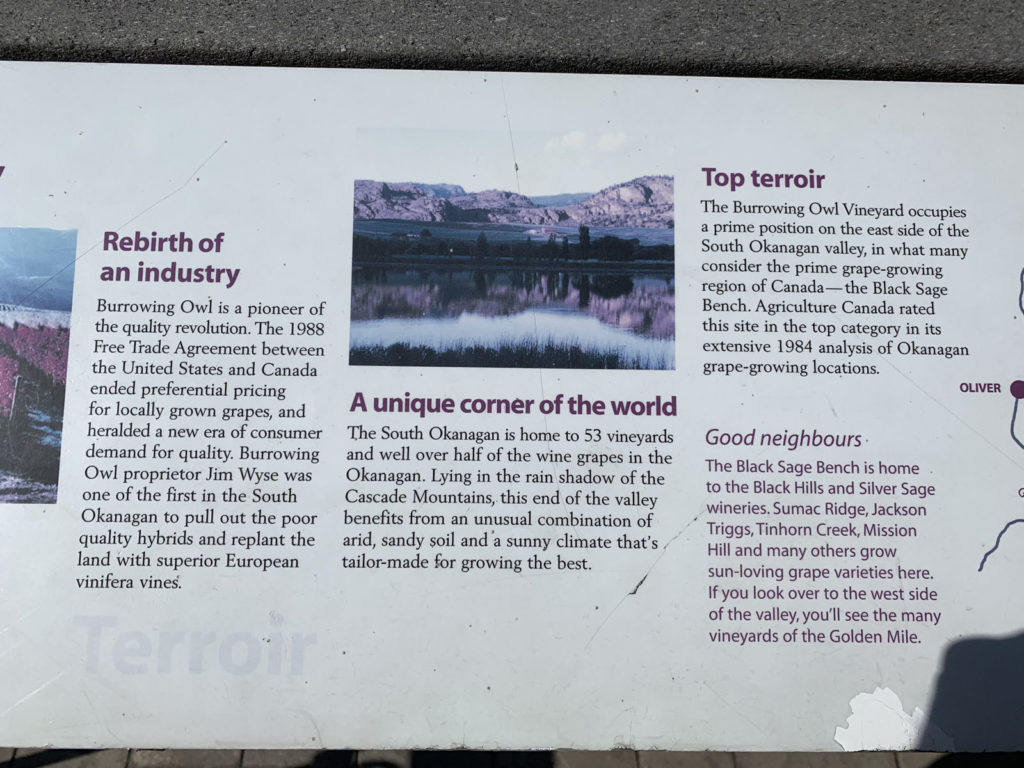

Bench – Many of the grapes are grown on benches, flat land between two slopes, so expect to hear about the Naramata Bench, Golden Mile Bench (the first officially recognized BC wine sub-region, in 2015) and Black Sage Bench, for example.

Meritage wines – Popular Bordeaux-style wines, mostly reds, from any blend of any combination of Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Petit Verdot, Malbec, St. Macaire, Gros Verdot or Carménère, with the first three most common. The term was coined in California, but it’s widely used in Canada.

Tasting fees – These vary and some wineries offer more than one option, flights of three or six wines, for example. Generally, plan to pay about C$15 per person, with one fee deducted if you buy wine. Plan to spend 30 minutes for 3 wines and to listen to a short spiel explaining what’s in your glass. If you are a serious taster and want to spit out the wine, you might find you have to ask for a spittoon.

Visiting the vineyards – It’s rare to find a vineyard where you’re free to roam on foot, among the vines, as we do in Switzerland. Larger wineries sometimes offer tours and make it clear that you’re not welcome unless you’re part of an organized walk. Burrowing Owl, in the far south, has found a good solution, with a short vineyard walk you can do unaccompanied as well as good, easy to follow educational information in the stairwell of the winery, with windows into the work areas, which allows you to take your time and absorb the basics of how the wine is made.

Wine clubs – These are huge part of the BC wine business. It makes sense, given that most Canadian wine consumers live far from this area. Expect to see and hear lots of encouragement to sign up to have wine shipped to you anywhere in Canada 3-4 times a year, with lots of perks, including free or discounted tastings and meals when you visit. Major wineries have good restaurants to show off food and wine pairings, so the clubs make sense if you live in Canada and plan to be a regular visitor.

Wine passports for mini-regions – there are several; ask about them.

Kelowna, the centre and Penticton, south

Two towns that served as useful markers for our car trip were Kelowna and Penticton (both with airports). Kelowna, the main town, was where I mistakenly assumed most of the wineries would be found. It is home to 20 wineries including some of the best-known. It turns out to be a good base and starting point for a drive south. Several of the wineries have patios for dining and tasting that give wonderful views up and down Okanagan Lake. The town itself is pretty, with the lake the focal point, a lively centre with a waterfront park, and it is ringed by hillsides. A short drive up Knox Mountain, from the city centre, gave us great views of the vineyards that spread out towards the south, as well as excellent hiking trails, the perfect way to balance driving and wine tasting. The park offers panels with a history of the region, including details about the massive firestorms of 2003 – not by any means the only major fire here. You come away with a new respect for the wineries along the lakefront.

Penticton is towards the south end of this 250 km long lake, and here you begin to notice the difference in climate – warmer, drier – more barren landscapes and rocky soils, as you move into the arid region. The town has several nearby wineries within walking distance, good for giving the designated driver a chance to do some real tasting. We stopped at the Great Estates wine education centre, which offers courses and daily tastings that change, from several wineries, with knowledgeable staff.

We then drove as far south as the southern tip of Osoyoos Lake, in the Sonoran Desert, which offers tourists another view of Canada complete with tumbleweeds and rattlesnakes; the Osoyoos Desert Centre is just 3 km north of the town of Osoyoos. From Nk’Mip Cellars you can see Washington State in the US, which is also on Lake Osoyoos.

But you’re in good hands right here in Canada.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.